Board Ballet: Choreographing the JV Board Agenda

An annual agenda that balances operational reviews with discussions of strategy and growth will help JV Boards be as effective as possible.

Good governance matters to the performance of joint ventures. Our Joint Venture Governance Index is a rigorous, independent, data-driven way to measure governance strength.

March 2020 — TWELVE YEARS AGO, we co-authored with CalPERS a set of guidelines for joint venture governance.[1]A version of this insight was previously published in the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance – see James Bamford, Geoff Walker, and Martin Mogstad, “Joint Venture Governance Index: … Continue reading At the time we argued, and still believe, that good governance in joint ventures strongly correlates with sustained financial performance, sound management of risks, and the ability of JVs to adapt to the changing needs of the market and their shareholders. We have asserted that joint venture governance is pound-for-pound more “physical” than corporate governance due to the unique nature of a joint venture’s relation-ship with its shareholders.[2]See James Bamford and David Ernst, “CalPERS Global Governance Principles: Joint Venture Governance Guidelines,” CalPERS, Updated Mar 16, 2015; James Bamford and David Ernst, “Governing Joint … Continue reading And while the number of shareholders is far more limited in JVs compared to those of public companies, the interests of the shareholders in JVs are more expansive, dynamic, and prone to conflict – which ultimately makes joint venture governance proportionately more demanding and consequential.

To bring greater transparency into how well joint ventures are governed – and to help investors, owner companies, joint venture Boards, and individual JV Directors calibrate the strength of the governance of ventures they own or have been appointed to oversee – we have developed a Joint Venture Governance Index. Like corporate governance indices, it defines a set of testable standards for governance that predict performance, and helps Boards and other stakeholders calibrate where they are relative to objective standards of governance excellence, peers, and their own historic performance.[3]For an overview of corporate governance indices see: Paul Gompers, Joy Ishii, and Andrew Metrick, “Corporate Governance and Equity Prices,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. … Continue reading Unlike corporate governance indices, however, the Joint Venture Governance Index is structured to address the unique governance demands of joint ventures – a highly-material class of businesses susceptible to shareholder misalignment, Board over-reach, and other ills derived from the nature of the joint venture ownership structure.[4]Because corporate governance indices are principally interested in identifying correlations between equity returns and governance policies, such indices generally focus on governance provisions … Continue reading

Governance in JVs matters. While JV governance is garnering more attention than it did a decade ago, the overall state of JV governance is still not good. Simply put, the pressures that have pressed many corporate Boards to up their games on governance have not been much in play in JVs. Public companies talk a lot about and actively track how they govern themselves, and listing authorities generally demand some form of governance assessments. It’s odd that companies don’t apply similar discipline to the governance of their JVs – especially given the materiality of joint ventures and the risk exposure these assets and businesses introduce.[5]From a materiality standpoint, many global companies, especially those in the aerospace and defense, chemicals, energy, and mining sectors hold 10 or more joint ventures which may account for at … Continue reading

Bringing greater rigor to JV governance is not straightforward, however. For starters, some concepts and best practices from corporate governance do not translate into a JV environment, which makes it hard to solely rely on corporate governance frameworks, tools, and standards in driving the conversation. For instance, corporate Boards do not need to oversee the conflict-laden operational interfaces and commercial relationships between the company and the shareholders, nor deal with committee members who are not on the Board. Furthermore, JV governance does not attract the same level of attention or time dedication from Directors. Our data shows that the median JV Director spends 15 days per year on their role, compared to 30-35 days per year for corporate Directors. JV Boards often lack the resources to support efficient engagement or focus on governance, whereas corporate Boards can usually depend on highly-professional and well-resourced corporate secretaries, investor relations, and legal departments to support governance and shareholder management.

Most importantly, JV governance is tougher to improve because it requires agreement among multiple owners, where Directors are not well-incentivized to speak up when the governance of a JV isn’t working well, and where the tone is frequently set by the least motivated Director. JV Directors are almost always current executives of, and nominated by, one shareholder, and are therefore not independent.[6]See James Bamford and Shishir Bhargava, “Independent Directors for Joint Venture Boards,” Corporate Board, February 2020. As such, the push to improve governance can be interpreted with suspicion or as self-interested by Directors from another shareholder. Meanwhile, if a Director speaks up, they run the risk of going against a more senior member of their own company or presenting a dis-united front to their partners and joint venture management.

Having an objective way to benchmark JV governance can be a useful way to overcome these obstacles and supplement JV Board and Director self-assessments. Calibrating the governance of a JV against an objective set of standards that define what “good” look like depersonalizes the conversation, cultivates a shared view among the Board of what constitutes good governance, and leads to practical suggestions that do not involve re-opening agreements. It also gives the shareholder companies, and their corporate Boards, a way to track and cross-calibrate the governance of their joint ventures.

The JV Governance Index we developed over the last decade includes 100-plus standards – that is, testable contractual terms and governance policies, practices, and behaviors – organized into nine core dimensions. These standards test for the presence of matters related to the overall governance model, Board size and composition, Board workings and procedures, shareholder and Board voting thresholds and delegations, committees and owner support, and other aspects of joint venture governance.[7]Depending on the structure of the JV and the objectives of the analysis, additional standards can be added under supplemental dimensions, including those related to shareholder-provided services, … Continue reading The standards reflect both good practices seen in corporate Boards (e.g., Board independence, presence of an audit committee chaired by a qualified financial expert, periodic Board and Director evaluations), and practices unique to the structure and challenges of joint ventures (e.g., conflict of interest protocols that describe how Directors should balance their fiduciary interests to the JV with the interests of the shareholder that nominated and employs them).[8]Joint ventures come in many different corporate forms and structures, which the JV Governance Index seeks to reflect. For instance, while many JVs are structured as separate legal entities (referred … Continue reading

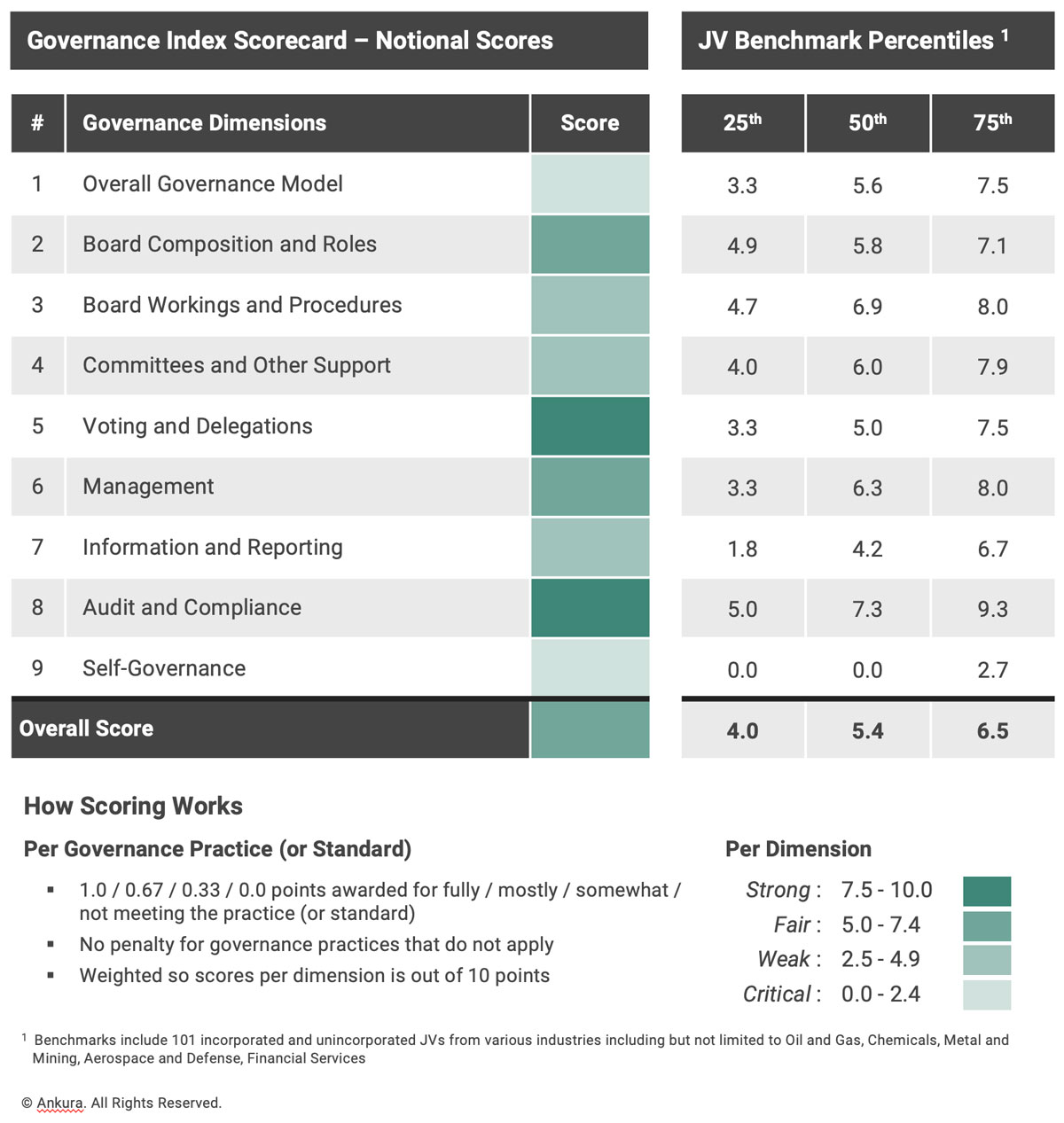

A notional scorecard is shown below (Exhibit 1). At a summary level, the JV Governance Index provides dimension-level scores and an overall score for a given JV, and also shows a comparison to other JVs within the benchmarking group.

To generate a JV Governance Index score, we review detailed non-public performance data, legal agreements, and governance documentation related to a joint venture, and conduct confidential interviews and surveys with key stakeholders, including members of the Board, committees, and management. These inputs allow us to evaluate each venture on numerous governance standards, testing for the presence and quality of specific terms and practices. For each standard, we assign the joint venture with one of four ratings (fully meets, mostly meets, somewhat meets, or does not meet) linked to a numeric value. We then roll-up these standard-level scores into dimension-level scores and an overall JV Governance Index score on a scale of 0-10. The selection of the standards and methodology underpinning them are based on our experience in more than 500 joint ventures over the last 25 years and more than 20 research studies we have conducted on different aspects of JV governance.

Using this methodology, we have assessed and generated JV Governance Index scores for 101 mostly large JVs from around the world. Of these JVs, the median overall governance index score was 5.4, with the 25th percentile venture scoring 4.0 and the 75th percentile scoring 6.5. More specifically, some 9% of JVs had strong governance performance, with overall score of 7.5 or higher on our 10-point scale, while 46% of JVs demonstrated fair governance performance with a score of 5.0 to 7.4. In contrast, 41% of JVs scored as weak and 4% as critical, with overall governance ratings of 2.5 to 4.9, or 2.4 or lower respectively.

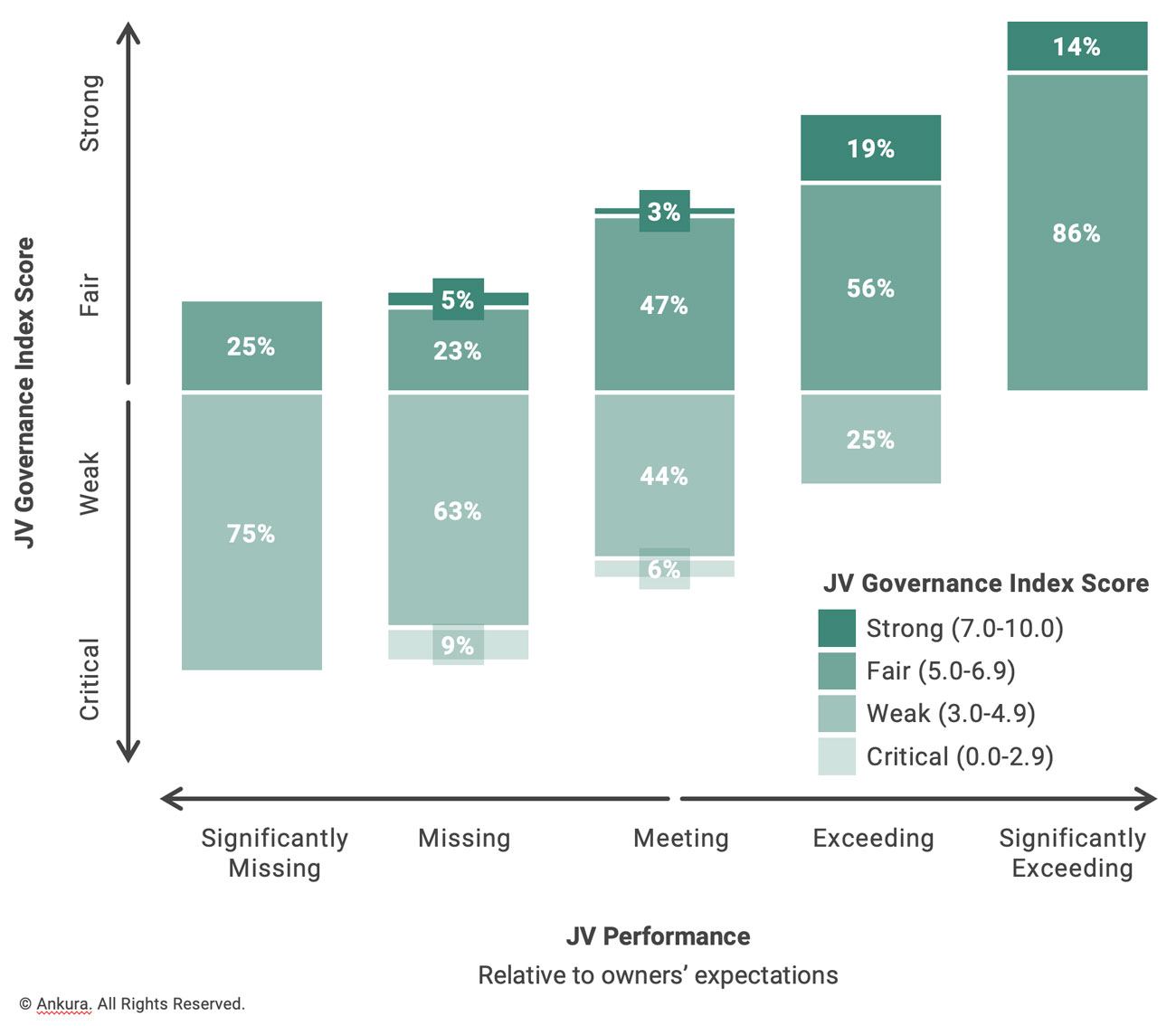

Notably, when we plot Governance Index scores against a joint venture’s financial and operating performance relative to owner expectations, we see that, on average, JVs with higher JV Governance Index scores are substantially more likely to show strong outcome performance, while those with lower scores are much more likely to be missing or significantly missing performance targets (Exhibit 2). This indicates a clear correlation, although not one-way causation, between good governance and performance of joint ventures.

Beneath these general patterns lay some important differences among industries, geographies, and corporate form. JVs in developed regions (e.g., North America, Europe, and Australia) perform better overall against our governance standards compared to JVs in developing regions (e.g., Middle East, Asia, and Latin America). Australian JVs performed best among all regions, with a median score of 6.0. Within industries, healthcare, financial services, petrochemical, and chemical JVs scored well, while mining and high-tech joint ventures performed worst. The oil and gas sector, where companies have more than a century of extensive experience with JVs, sits in the middle of the pack. When we compared incorporated and unincorporated joint ventures – i.e., those where a separate legal entity was established vs. not – we found no material differences.

In scoring joint ventures against the JV Governance Index, our analysis also shows patterns of strong and weak performance at the individual governance term and practice level within each dimension.

Overall Governance Model. At the highest level, it is the duty of the JV shareholders and Board to define the operating and governance model of the venture – i.e., how shareholders will relate to the venture, their shared expectations with regard to the venture’s strategy and evolution, how engaged the Board and committees will be relative to management, and how the different elements of governance work together.

While most JVs define some of these matters in their corporate bylaws and shareholder agreements, such legal documents rarely provide sufficient guidance on how the governance system is intended to work at a practical level. Our data shows than only 45% of JVs have a Board-approved Governance Framework or equivalent document that establishes integrated expectations for how the governance of the venture is designed to work and “how the shareholders want to govern this place.”[9]For addition information on JV Governance Frameworks, please see: James Bamford, “Operationalizing Joint Venture Governance,” The Joint Venture Exchange, August 2017; and James Bamford, David … Continue reading JVs that meet this standard tend to unlock higher overall governance scores.

Board Composition and Roles. Our analysis shows that JV Boards are almost never fundamentally the wrong size – i.e., less than four or more than ten Directors.[10]We make an exception under the standard for JV Boards to be larger under special circumstances – e.g., public shareholders, or more than 10 partners, such as the Star Alliance or SWIFT. For more on … Continue reading Unlike corporate Boards, which tend to become too large, thereby making full-Board discussions difficult and muting individual Director accountability, JV Board size is usually contractually-defined within an appropriate range. That said, JV Boards often have far too many people in attendance, including non-Board functional experts from the shareholders and the full management team, which can swell the people in the Boardroom to 15 or 20 or more. We believe that when JV Board meetings are filled with “back-benchers” – i.e., shareholder functional staff and full contingents from venture management – Board discussions are less open and probing, more prone to grand-standing, and less inclined to compromise. Perhaps most importantly, such expanded attendance tends to undermine the Board building a collective sense of self.[11]This expected practice does not prevent non-Board members from attending Board meetings – but, rather, seeks to limit and focus that participation. For example, we fully expect (and encourage) the … Continue reading

JV Boards also tend to do well on other aspects of composition. For example, our sampled JV Boards are mostly composed of individuals who collectively possess the balance of skills, experience, knowledge of the JV company and its markets, and functional expertise to enable the Board to effectively discharge its collective duties and responsibilities to oversee management and governing the company. In addition, the JVs in our data set generally have at least one Director from each shareholder who is truly able to represent that shareholder’s interests and command internal resources to support the venture. This practice gets at the heart of what it means to be a Lead Director – i.e., a Director who positioned to directly and actively support the JV, make things happen inside their own companies, and coordinate the company’s other JV Directors.

By contrast, too few JV Boards have Directors whose annual objectives and performance reviews include any direct link to their role on the Board. To be clear: a typical executive sitting on a JV Board might spend 8-20 days per year in this governance capacity (with a median of 15 days) – so we do not expect their annual objectives or reviews to principally focus on the JV. What we do expect is that the JV and the role of the Director should feature in such discussions and, at a minimum, reflect the amount of time spent serving as a Board member.

Board Workings and Procedures. Most JV Boards do fairly well on delivering on basic governance procedures – for instance, conducting regular independent financial audits, establishing confidentiality provisions for all Directors, maintaining an action log for Board decisions, creating a whistleblower system, and having a process that enables the Board to take smaller decisions (e.g., budget adjustments, insurance policy renewals) between official Board meetings through the use of a written consent process, such as email circulars.

That said, JV Boards tend not to do a good job on managing how they spend their time. Specifically, our data shows that JV Boards tend to spend too much time on financial and operational matters – and not enough time on strategy and talent management. On strategy, the role of JV Boards is often insufficient and unclear, and is not well-supported by materials and conversations initiated by management. On talent, JV Boards spend only 5-10% of their time on average on succession planning, managing secondees, or on talent engagement or overall value proposition to venture employees.

Director on-boarding and training is another area weak spot in JVs. Specifically, JV Director training programs often focus on issues germane to corporate Directors (e.g., fiduciary duties, Director liabilities), but not the unique needs, challenges, and risks facing JV Directors (e.g., managing anti-trust risks in JVs with competitors, navigating a dual duty of loyalty to the venture and a shareholder, and managing shareholder information requests on JV management, including those from non-Board members).

Audit and Compliance. While JVs generally perform well in the area of audit, controls, assurance and compliance, one gap is worth noting. Our analysis shows that JV Boards often do an incomplete job making plain how the JV is expected to comply with and provide assurance against the shareholders’ corporate standards and policies. This includes how management should approach shareholder expectations to achieve “material equivalency” in such areas of safety, environmental compliance, business ethics, and financial controls, and what management should do when the shareholders hold different corporate standards.

We believe it is the role of the Board to provide clear guidance to management these areas, to harmonize any differences among the shareholders, and to directly and forcefully communicate to their own organizations regarding this expectation. A failure to do this can result in a severe “governance tax” imposed on venture management.

Self-Governance. Also concerning is the finding that JV Boards are underperforming across virtually all aspects of good self-governance. Far too few JV Boards have established and agreed to criteria for evaluating the governance system as a whole and conducting periodic reviews of this system. Even more narrowly – and more fundamentally – few JV Boards have defined expectations for the Board itself, annually reviewing their performance against these expectations, having a structured conversation about gaps and improvement opportunities. This lack of self-governance then cascades into a failure of individual Directors to self-assess their own performance. Good self-governance lies at the heart of good governance.

Absent any review of the governance system, the Board, or individual Directors, it is simply a matter of luck – or great collective, raw instincts – to have a JV Board that performs consistently well across other dimensions of Board governance.

Good governance matters to the performance of joint ventures – and joint venture performance matters to public companies and their shareholders. As such, it is time to bring greater rigor, independence, and comparative data to measuring the state of governance in joint ventures. The Joint Venture Governance Index is an objective and powerful way to do this.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.

Comments