Q&A with Two Independent JV Directors

Flo Lugli of Global Hotel Alliance and Jason Mann of Life and Specialty Ventures

JV negotiations are only the first battle – once a JV is established, another wave of problems awaits.

APRIL 2016— SEASONED DEALMAKERS tell us that joint venture is a four-letter word. JV CEOs assert they have the toughest job in business. And many operating executives confess they would choose exile in Siberia over a joint venture rotation. These attitudes are not surprising, especially given how often JVs fail to deliver on their shareholders’ strategic, financial, or operational expectations. Ankura’s research on joint venture performance has consistently shown at least half of JVs fail on one or more of those counts (Exhibit 1), among other sobering statistics.

The result of this failure? Many JVs limp along for years, consistently underperforming against expectations. Others are mercifully terminated by parents seeking an end to the bleeding. And some collapse spectacularly in a sea of recriminations and lawsuits. Some degree of failure is inevitable in business. New technologies sometimes do not work. Markets often do not materialize. Old needs can disappear. Regulations change.

Joint ventures are not immune to these ills. Ask Verizon, which pulled the plug after only one year on a video streaming JV with Redbox that failed to gain traction against Netflix. So too with Iridium, a 19-partner satellite phone JV that collapsed into bankruptcy nine months after launch in the face of massive upfront capital expenses, buggy technology, and poor commercial appeal.

"*" indicates required fields

But aside from these normal business challenges, joint ventures can also fall victim to other diseases caused by their unique ownership structure. Ankura has served hundreds of JVs and conducted dozens of research studies over the years, giving us a front-row seat to the multitude of creative ways that JVs implode – and providing us insight into how to inoculate against those outcomes.

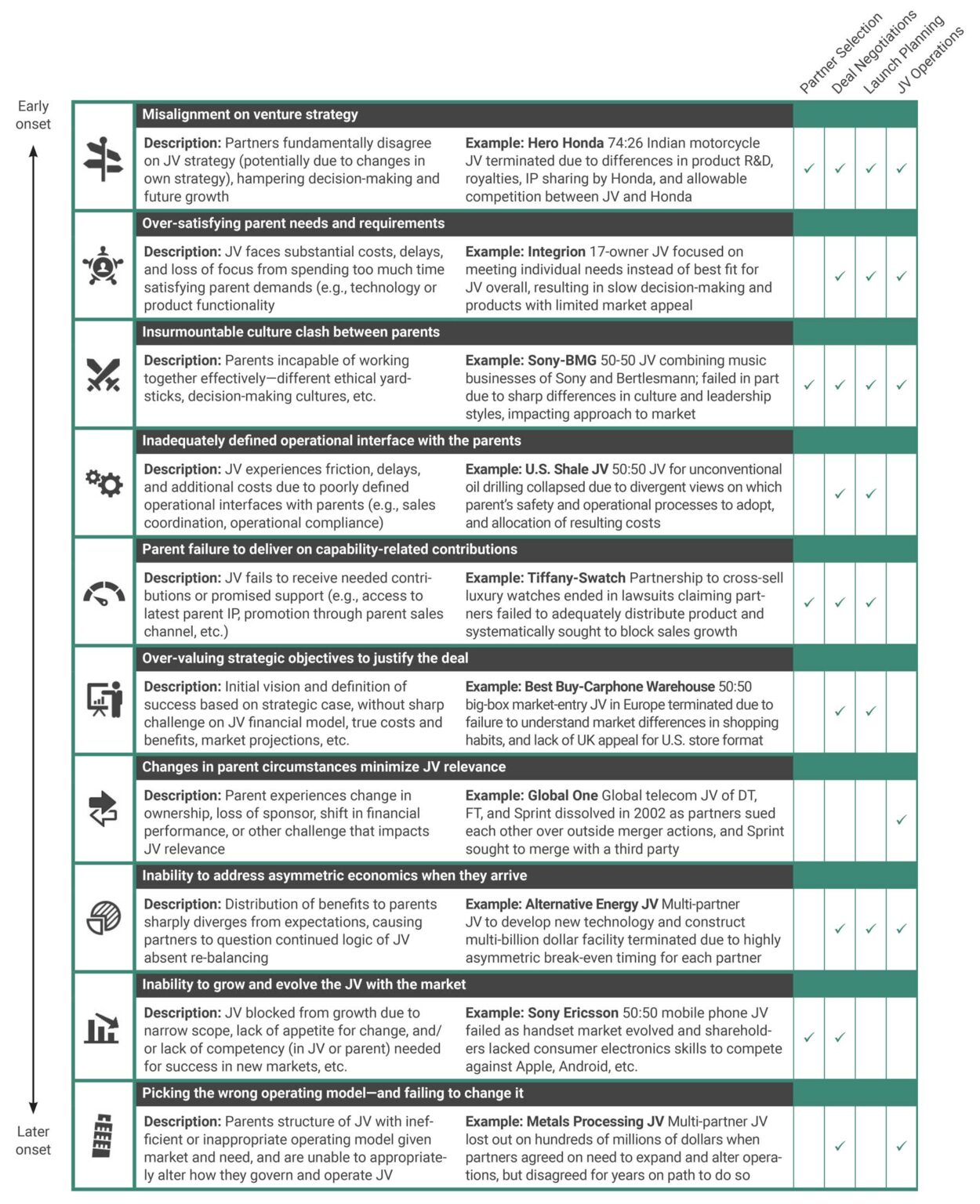

Most joint venture failures are rooted in one or more of ten common causes. Some are more likely to occur early in the life of the JV; others tend to emerge as the venture reaches middle age. Keeping these failures at bay requires focus across the venture lifecycle, putting the onus on dealmakers, JV Board Directors, and JV CEOs alike for diagnosis and treatment (Exhibit 2).

Source: Examples drawn from public filings and press reports; Ankura Consulting Group

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Maintaining agreement on strategy is not easy when reasonable minds can disagree – or when the shareholders are moving in separate directions. Our benchmarking of alignment between JV partners shows that 69% are at odds on long-term strategy, and 58% cannot agree on the JV’s upcoming annual budget.

Partners that disagree on strategy often provide conflicting guidance to JV management, creating confusion and delay, and forcing the JV CEO to spend time and effort overcoming internal owner differences (instead of focusing on running the business). This is especially problematic in fast-paced markets such as high-tech, media, and telecom, where real-time decisions are required, and initiative is lost in the face of multiple Board cycles to achieve shareholder alignment.

Some solutions: During the deal phase, companies can take a number of powerful but novel actions, including conducting strategic partner due diligence; using misalignment scenario planning to uncover frictions and test solutions; structuring scope and right to expand; and pre-agreeing on a multi-year JV business plan. During launch planning and beyond, companies should consider appointing to the Board senior executives with real internal clout and an aptitude for strategy; holding annual Board strategy off-sites; and establishing processes for handling misalignments when they emerge.

In its early days, the Star Alliance – a global airline partnership now owned by over 30 companies, including United, Lufthansa, Singapore Airlines, All Nippon Airways, and Thai Air – was so focused on satisfying every owner requirement that The Economist observed, “Star has no fewer than 24 committees to sort out such matters as network connectivity, purchasing, and customer relations. Chairmanships have been spread around to keep everyone happy. For those involved, it makes even Airbus Industries seem like a model of industrial efficiency.”

JVs have an understandable but dangerous instinct to try to satisfy every owner request – to build this product “bell” and that service “whistle” – instead of focusing relentlessly on the customer and what is realistic. This instinct leads to project delays and ballooning costs, and can sow the seeds of unhappy partners who eventually withdraw support from the monster they created.

When JVs are designed to act as a shared utility for three or more owners, they are particularly susceptible to lobbying for individual parent needs. A series of financial service industry JVs suffered from such infections. Integrion, an e-banking joint venture that included IBM and numerous major U.S. banks as owners, collapsed under the weight of a feature-laden product designed to meet the individual needs of 17 squabbling owners, without doing any one thing well.

Some solutions: Companies can take a number of steps to promote collaboration and balance, including crystallizing in the deal that parents are responsible for paying JV costs to meet their individual requests; developing a set of Guiding Principles during launch, which spell out what parents can and cannot ask the joint venture to do; appointing an independent Board Director to inject an impartial voice when reviewing parent requests; and formally tracking and reporting to the Board on the nature, timing, and costs incurred by responding to parent requests for support.

One highly successful healthcare IT joint venture we work with allows each owner to fund up to five software developers within the venture to design features that meet owner-specific requirements. Those developers are hired and managed by the JV – but their fully loaded costs and work program are the responsibility of the owner.

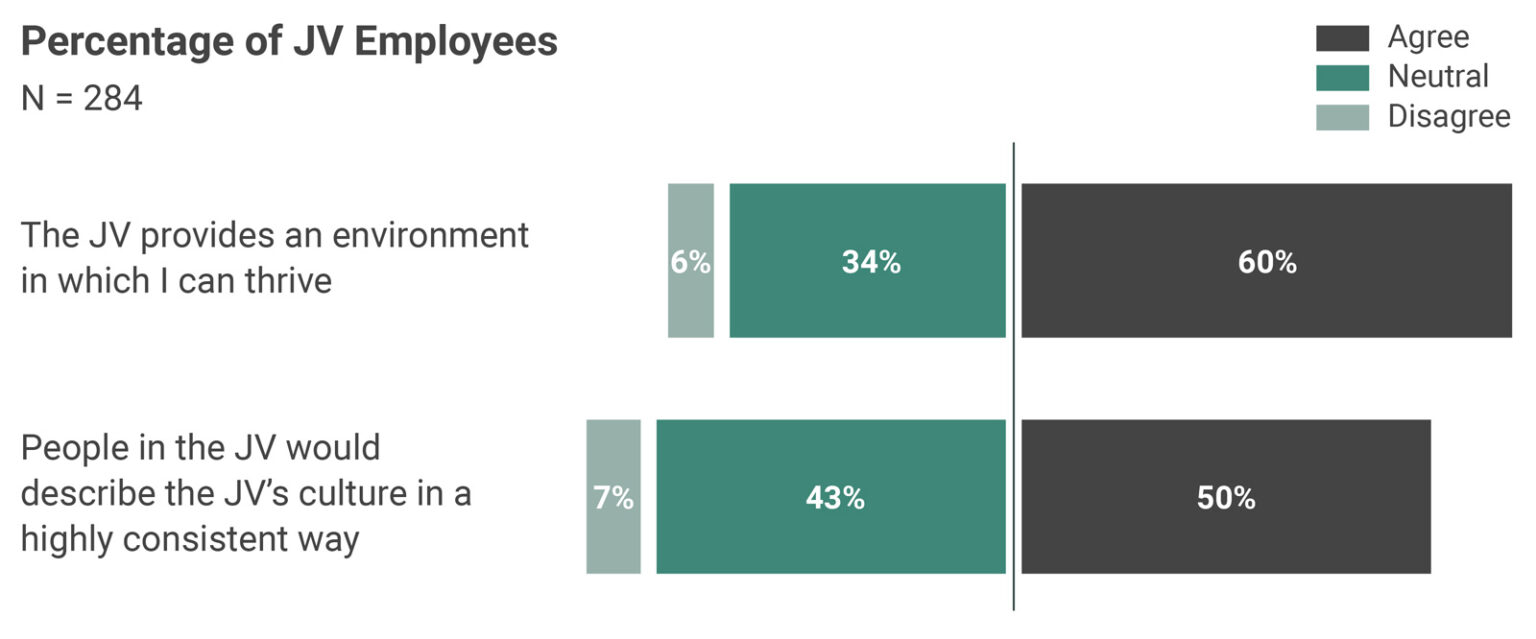

Many ventures are doomed to failure because the partners are incapable of working together effectively. At its most benign, this reflects the difficulty of bridging cross-border cultural differences to create a cohesive and effective JV culture. Our research shows that only half of JV employees have positive things to say about the culture inside their JV (Exhibit 3).

Source: Ankura JV Employee Engagement Benchmarking

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

At its worst, culture clash is caused by a partner who demonstrates a different ethical yardstick, as Walmart discovered in India when its JV with Bharti was rocked by allegations of local bribery and corruption. Or it comes from a partner who views the relationship as a one-way street to extract value with no intent of collaborating, as Danone discovered when its Chinese partner, Wahaha, secretly manufactured and sold identical JV products outside the JV.

Some solutions: Early on, companies should ensure that due diligence focuses deeply on a potential partner’s corporate culture, values, and decision-making – including talking to their counterparties in other partnerships. During the deal, the partners should write legal agreements that specifically require the venture to adopt the strictest shareholder policies and processes for ethical conduct. During launch, the JV team should hold joint workshops to identify cross-border cultural differences and communicate expectations as to how the JV’s own culture should function – including ethical guidelines.

Joint venture legal agreements say little on the day-to-day structure of operations, and that space must be filled in by launch teams from the shareholders. In some cases, this process fails to sharply define which partner’s processes and systems the venture will utilize, causing each parent to bombard the venture with overlapping and sometimes contradictory expectations. In other cases, the parents agree to import one partner’s processes and systems without adapting them to the venture’s situation. Our research shows that these kinds of mistakes during launch can erode up to 50% of venture value.

Consider the case of a $10 million startup biofuels JV, which was expected to match every one of the corporate processes of its large-cap global owner, as if it were an internal business unit. The JV was saddled with a structure that destroyed its entrepreneurial spirit, and costs that made it uncompetitive in the market.

Some solutions: During the deal, companies should begin thinking through operations early enough to drive certain guidance into the deal itself – like what reporting and information is required, or the source of key systems and processes. After deal close, the partners should invest in a launch process that produces a blueprint for the JV’s operating model – and captures the JV’s internal organization and staffing, how money will be made, and the JV’s level of independence from shareholders within each business function. A robust Operating Model Blueprint also includes process maps for key decisions, an articulation of the JV’s policies and processes, and a plan for the JV’s reliance on parents for services. This blueprint should be made into a core reference for parents, the Board, and JV management.

Joint ventures are fundamentally about combining the parents’ assets and capabilities in unique ways to unlock opportunities that neither partner could access alone. Legal agreements usually obligate a shareholder to contribute capital and certain assets (such as brands, factories, and customer contracts) to the venture. But the most important contributions to a JV are often capabilities– skills, technologies, processes, relationships, and ways of working. And these are notoriously hard to adequately define within the legal agreements.

By contrast, JV legal agreements may include some form of technology licensing or service agreement that specifies the venture’s access and rights to certain known technologies, such as software or systems. But these deal terms often miss the more implicit capabilities, such as know-how, expertise, and market relationships. To handle this, legal agreements tend to rely on ownership interests and broader financial incentives to motivate the parents to do the right thing.

But this is an imperfect – and often flawed – solution. For instance, in an Asian beer joint venture in which a global brewer purchased a 50% interest in a local brewer, half of the $200 million in expected value was to come from sales and marketing synergies. These synergies were almost entirely based on the assumption that the global brewer would deliver new, cutting-edge branding, marketing, and sales techniques to the venture, which had an antiquated approach to customer loyalty, demand generation, and distributor management. Unfortunately, the global partner failed to second top sales and marketing staff into the venture – and those that they did place in the venture had no experience in Asia or emerging markets. Adding salt to the wound, the JV struggled to get access to experts and the latest marketing techniques back in the parent. The net result? Half of the anticipated deal value never materialized.

Some solutions: Companies should define all tangible and intangible contributions with specificity, and structure incentives into the deal to encourage shareholder follow- through (e.g., financial penalties or exit rights for failure to deliver). For example, an Asian pharmaceutical company that entered into a JV solely to learn a U.S. biotech partner’s scientific capabilities came up with a creative approach. They structured the JV agreement to include more than two dozen specific Key Learning Landmarks (KLLs) – like the ability to design a new product, or to perform an analytic technique – that the partner was expected to deliver. The agreement then linked meaningful financial payouts and penalties to the delivery or non-delivery of these KLLs.

Once the deal is done, companies should consider putting senior Directors on the Board who have the internal clout to ensure that the JV receives key contributions; building a formal parent-endorsed learning agenda to document the nature and timing of intangible contributions to the venture; and using annual scorecards to track parent performance in delivering those contributions.

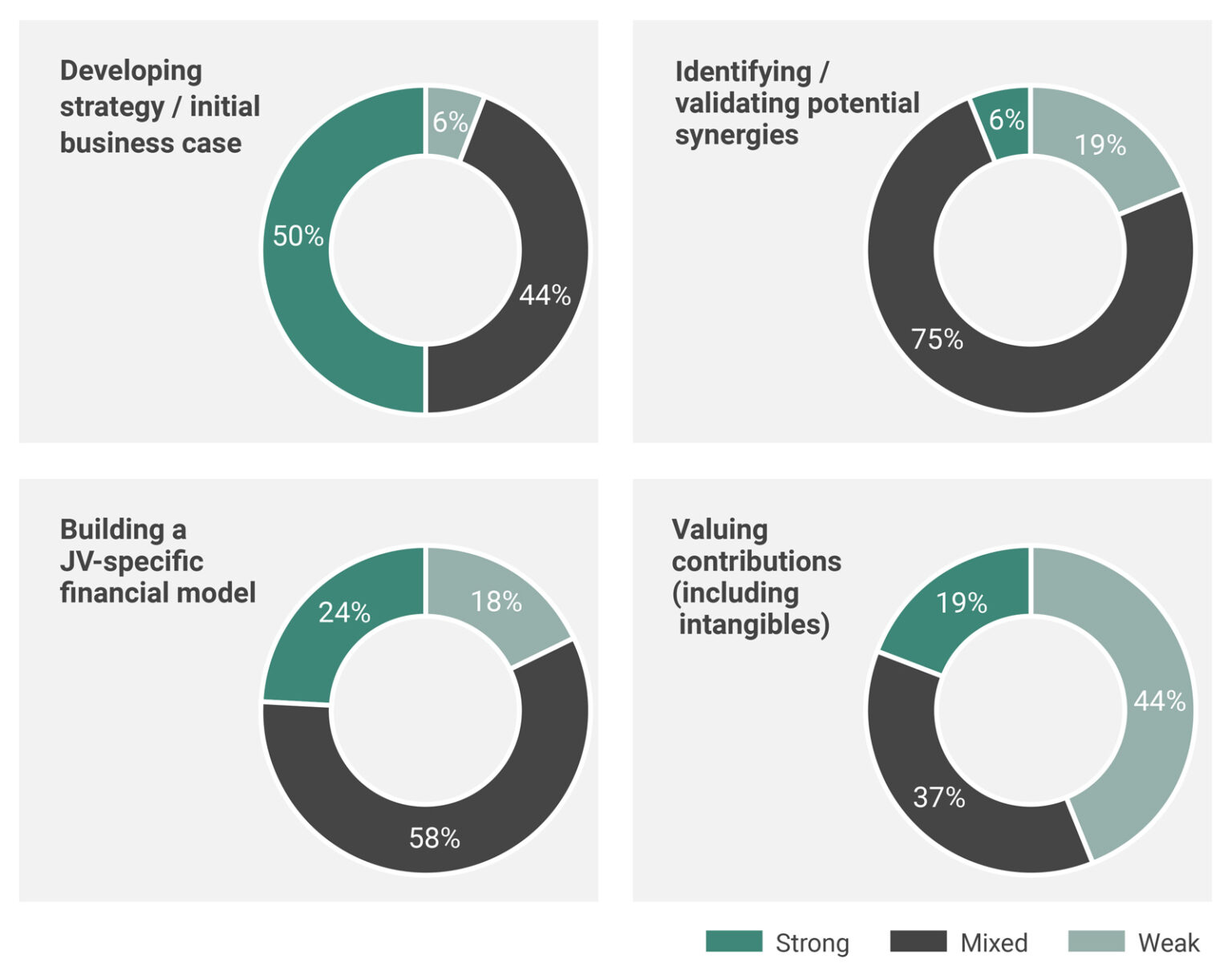

Ventures are often sold internally as a way to achieve strategic objectives like market access, future positioning, or learning. That is not the same as having a strong financial and business case. JVs are notoriously hard to model, with their various opaque financial flows and parent-JV economic relationships. Strategic interest in an opportunity can overwhelm sharp inquiry into cost and revenue predictions, making it hard to internally reject opportunities. Only half of JV dealmakers believe that they are strong at building a JV business case, and only a quarter believe that they are good at JV financial modeling (Exhibit 4).

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved

What’s more, internal sponsors may be promoting the JV based on speculative assumptions about the indirect benefits it will unlock for the broader business. For example, a slate of defense companies invested almost $1 billion in forming an emerging market JV to provide aircraft maintenance. The business case envisioned the JV winning contracts from multiple regional countries, while unlocking access to more equipment sales. Six years later, not a single service contract has been won outside the host nation, and limited sales could be traced back to the JV. When partners are not honest internally (or with each other) about if, how, and when the JV itself will make money, eventually the bill comes due.

Some solutions: Companies should require deal teams to generate a business case with the partner that defines specifically where and how the venture will make money; subject these business cases – particularly for large, strategic opportunities – to an internal review and challenge process by senior leaders who can say no; map the Total Venture Economics to understand the direct and indirect benefits of JV ownership for every partner (and to validate internal assumptions about indirect value creation solely for the company); and hold JVs to the strictest of financial assumptions, including tougher hurdle rates than wholly-owned projects.

JVs can quickly fall out of favor inside a parent company as the parent’s financial condition deteriorates or its ownership structure changes (e.g., it merges with or is acquired by another firm) – or as key senior leaders who internally sponsored the JV depart from the company. Whether these changes lead to benign neglect or outright starvation of necessary capital and other support to the venture, they can destroy an otherwise-successful JV. The Global One telecom JV between Deutsche Telekom, France Telecom, and Sprint was on path to deliver industry-leading capabilities, and was buoyed by high customer ratings. It came undone quickly as two partners sued each other over M&A activities outside the JV, and the third partner sought a merger that would force its exit from the venture.

Some solutions: Dealmakers should use strategic partner due diligence to uncover tenuous financials before getting into bed with a partner. If a deal is done, companies should build relationships with multiple senior executives in the partner, as well as selected future leaders in the next tier down, in order to build ties that can weather any storm.

Ownership shares and profit distributions are typically defined in the JV agreement – but dividends are rarely the only economic relationship between the parent and the JV. Most ventures have a web of supply and offtake arrangements and service contracts with their parents, who are also seeking ways to maximize the indirect value that the JV creates – by unlocking doors to new customers, enabling bundled product offerings, satisfying regulators, etc.

These diverse streams of JV returns to shareholders can lead to huge asymmetries in value creation for each parent. For example, a detailed financial model of a four-partner alternative energy industry JV based on a radical new technology revealed significant differences in projected NPV, cash flow profiles, and break-even results for each partner, due to how capital contributions, offtake rights, and other obligations were structured (Exhibit 5). These asymmetries were large enough to threaten the JV’s continued existence. Indeed, that future instability led one partner to pull out, which then led to a collapse of the venture.

One executive described partner imbalance in these terms: “At some point, usually pretty quickly, an asymmetry will reset itself, because if the losing partner cannot get to a win, it usually can make the other partner lose…so then the venture becomes lose-lose for a period, and the partners either find a way to make it win-win, or they exit.”

Some solutions: When structuring a deal, the deal team should map the Total Venture Economics to understand the direct and indirect benefits of JV ownership for every partner; negotiate an ownership split that appropriately reflects all direct and indirect sources of value creation; structure JV-shareholder supply or service relationships with arms-length pricing (and mechanisms for audit, benchmarking, and re- negotiation); and give the JV CEO full flexibility over sourcing services (including shifting to third parties) in order to limit the most contentious value discussions.

Markets are constantly shifting, as competitors deploy new products, disruptive innovators appear, and consumer tastes change. Like any other business, a JV needs to change to stay relevant. When JVs cannot change – because the shareholders’ agreement is too narrow and there is no appetite to change it, because parents cannot provide a capability the JV needs to evolve, or because JV management lacks the capabilities and skills needed to successfully lead the business in a new direction – then the JV is likely to begin a long trip toward oblivion. Consider the Sony-Ericsson JV, which went from the world’s fourth-leading mobile phone manufacturer to an afterthought as consumer tastes shifted, and as the shareholders lacked a competitive solution against the likes of Android and Apple.

Some solutions: Companies should work with the partner to identify potential business and ownership evolution paths during the deal phase; map out a playing field of products and geographies into which the JV will be allowed to grow without rejection from its parents; and design the JV agreement with pre-agreed methods to collaborate on evolving the JV when the future arrives (e.g., provisions for making changes to ownership, governance, delegations of authority, scope, capital investment, or other terms that impact the JV’s market strategy).

A key issue in structuring a JV is defining the JV’s desired overall level of independence from the owners – including how dependent the venture will be on parent company secondees, systems, processes, and services, and how the owners will relate to each other. We call this the JV’s operating model. Parents do not always strike the right level of independence, saddling the JV with a structure that is ill-defined, outdated, or incapable of succeeding in the market to deliver on the shareholders’ strategic, operational, and financial objectives. Natural resource JVs are especially susceptible to this problem, as evidenced by the rocky performance and eventual operating model restructuring of JVs like Kashagan, Syncrude, and Altura Energy.

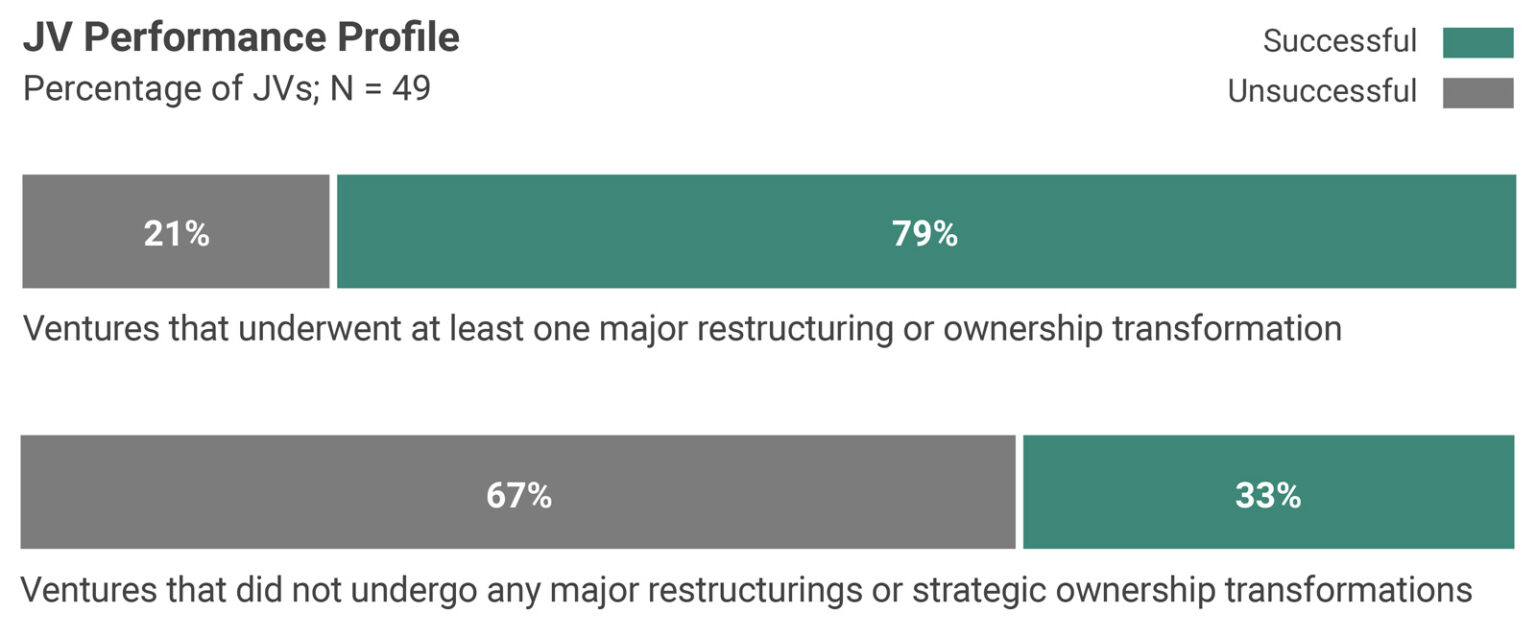

But making a change to the operating model is no small task. JVs must navigate through thorny shared decision-making that slows the pace of needed revisions. Our benchmarking of 150 JVs revealed routine delays of as much as 30 months in making necessary structural changes, with 10 to 30% improvements in operating income when the restructuring was finally allowed. Take the example of a multi-billion-dollar metals industry JV designed to process raw materials on behalf of four parents. The shareholders generally agreed on the appeal of operational improvements and capacity expansions offering $1 billion in revenue increases but bickered for years on the details. By the time they agreed to restructure, hundreds of millions of dollars in profit had been lost. Other JVs are not so lucky – they never reach agreement. Not surprisingly, restructuring that leads to improvements in the JV’s bottom line also contributes to overall success. Our research shows that 79% of JVs that are able to make structural adjustments are viewed as successful, versus 33% of ventures that remain unchanged (Exhibit 6).

Source: “Your Alliances Are Too Stable,” Bamford and Ernst, Harvard Business Review

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Some solutions: JV partners should consider whether the operating model should be independent, interdependent, or partner-operated based on the JV’s phase, scope, synergies, and need to leverage shareholder skills; negotiate a JV agreement that contains formal restructuring triggers (based on defined metrics); build a formal review process into the governance system to test whether operating model changes are needed; and make the Board Chair and JV CEO responsible for taking stock of needed venture changes on a regular basis.

Beyond these ten main causes of JV failure, two other areas – poor governance, and weak organization and talent – are often associated with JV distress. These areas are unlikely to directly cause JV failure on their own. Rather, they are a form of internal bleeding, and tend to compound the difficulty of addressing issues mentioned above.

Governance: Having a governance system that is simply too cumbersome to function allows some illnesses to take root. Consensus decision-making can lead to damaging delays and deadlock in fast-paced industries, and exacerbates the challenges of setting a strategy or evolutionary path for a JV. Consensus is a key part of JVs – but the most successful JVs also have governance systems with built-in pressure-relief valves to overcome disagreement, enable decision-making, and keep all parents pulling in the same direction.

Organization and Talent: The other key enabler of failure is not building an effective JV management team and organization. Has the JV managed to get access to and retain top secondees from the parent companies? Has the JV developed a compelling employee value proposition for those working directly for the venture? Has the Board delegated sufficient authority to JV management to be able to run and grow the business, thereby unleashing the JV’s entrepreneurial energy? Is the JV organization adequately insulated from shareholder overreach into operational details – or does the organization suffer from a “joint venture tax” where far too much time is spent responding to shareholder needs? Joint ventures that do not have good answers to these questions will find it extremely difficult to attract, retain, and motivate staff, and to respond to all the other threats that await them.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.